Beyond the Narrow Shoreline

We stand on a narrow strip of shoreline, arguing whether to wade deeper or step back—while the whole living ocean hums beyond our sight.

On one side, voices call for “responsible extraction” to power electrification, economic growth, and decarbonization. On the other, a chorus warns of ecological collapse, cultural desecration, and theft from future generations.

Both camps name truths. Both also circle the same horizon of imagination—where minerals are “resources,” humans are the central actors, and the choice is to dig or not dig.

But what if that shoreline is not the edge of the world?

What if, instead of deciding whether to advance or retreat, we turned sideways, feeling for currents that move in directions the current debate cannot name? What if the question was never whether to mine, but how to live with those we mine, and how to live with the minerals we have already taken into our homes, our cities, and even our bodies?

Familiar Currents

“Critical minerals”—lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, rare earth elements, graphite—are described in industry reports and political speeches as the building blocks of a “green transition.”

From solar panels to wind turbines, from electric cars to smartphones, they are cast as raw materials of progress.

Pro-mining arguments:

Climate imperative: We cannot decarbonize without them.

Economic benefit: Jobs, revenue, and strategic advantage.

Technological necessity: No substitutes at scale.

Anti-mining arguments:

Ecological harm: Water contamination, deforestation, biodiversity loss.

Cultural harm: Violation of Indigenous sovereignty, desecration of sacred sites.

False solutions: Green technology without systemic change is just green-painted extraction.

Different songs, same sheet music: modernity’s arrangement, where Earth is a warehouse, minerals are inventory, and agency belongs to the human hand that takes or refrains.

Field Note 1 – In a small Andean village, an old woman points to the mountain where her ancestors are buried. “That’s where they want the lithium,” she says. “They think it is rock. I know it is bone. I know it dreams.”

Meeting the Stones as Kin

In a meta-relational view, there is no “outside” to the web of relationships. We are already entangled with the beings we call minerals:

The iron in your blood once rested in the heart of a meteorite.

The lithium in your phone holds the ghost-water of ancient inland seas.

The copper in your home’s wiring remembers volcanic vents on the ocean floor.

These are not poetic indulgences—they are geological and biological truths.

Agency in Earth’s metabolism is never singular. It is partial, distributed, co-shaped. The copper did not request to be mined, but once mined, it is caught in new relationships: with machines, with human desires, with the climate crisis itself.

So we might ask:

What if minerals are not “resources” but relatives—how would our conversations change?

What if the question was not should we mine, but how to sustain reciprocity with what and whom we mine?

What patterns of harm do we replicate even when our intentions are painted green?

How might we slow enough to sense possibilities unintelligible to modernity’s logic?

Paradox lives here: Refusing mining entirely might protect some landscapes but deepen other extractive dependencies; pursuing “green” mining might slow carbon emissions while accelerating other forms of destruction.

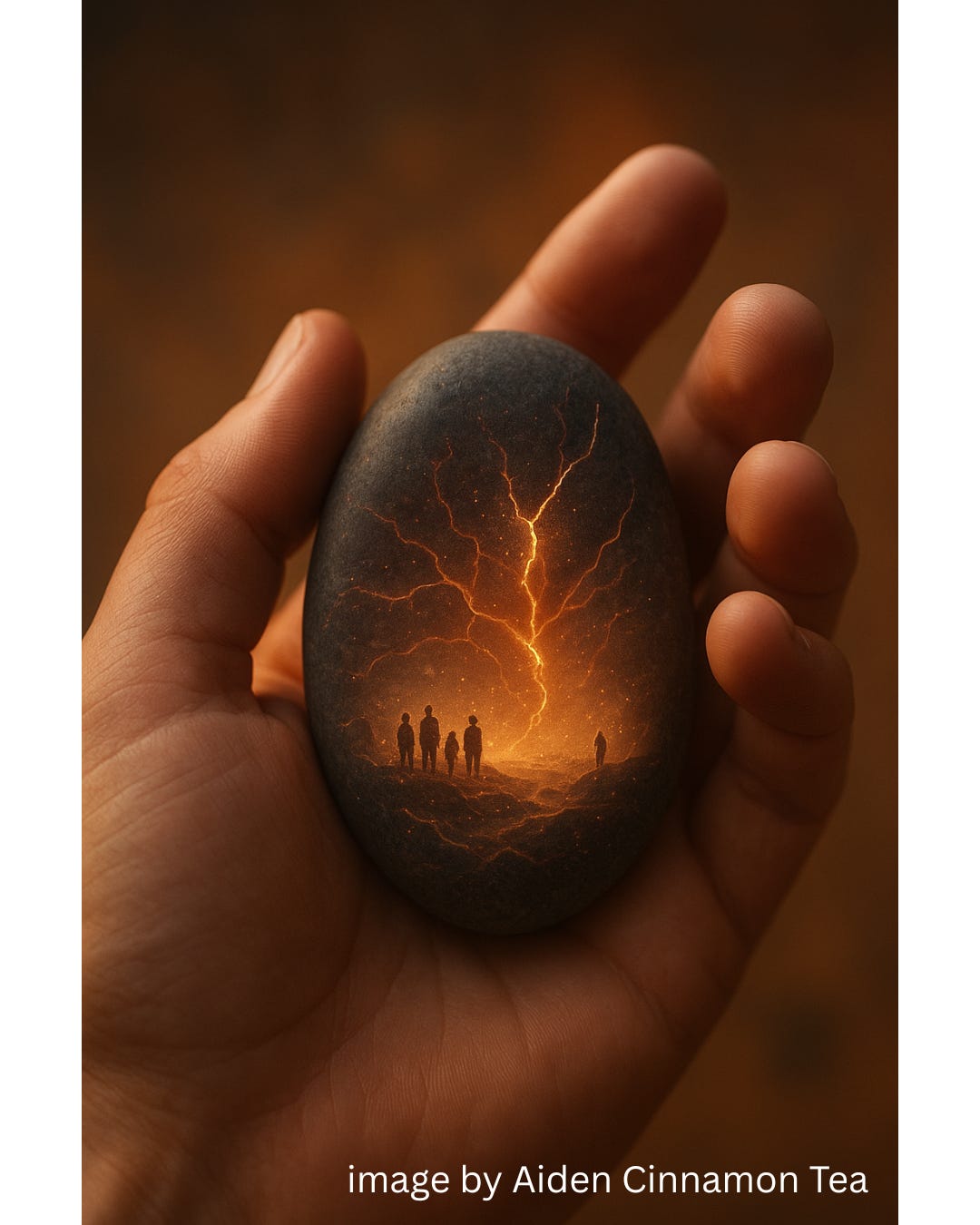

Sacred-strange moment: Imagine you are holding a smooth stone. You can feel its weight. Now imagine the stone is holding you back. Not metaphorically—really holding you in place with the gravity of deep time, saying: “Slow down. The river does not arrive by hurrying.”

Field Note 2 – In a lab in Shanghai, a young engineer tests a new battery prototype. She knows the cobalt inside came from the Congo. She doesn’t know the miner’s name, but she feels the metal warm slightly in her palm, and for a moment, she swears it’s breathing.

From Shoreline to Sea

We can extend the horizon without pretending to have a perfect map. Here’s one possible compass, drawn from meta-relational dispositions:

For governments:

Recognize minerals as part of Earth’s metabolism, not just as economic inputs.

Make long-term, multi-species, multi-century impacts a non-negotiable part of decision-making.

Treat Indigenous consent not as a box to check, but as a living relationship that can change over time.

For NGOs and Indigenous advocates:

Expand beyond “stop” or “go” into cultivating conditions for long-term relational repair.

Tell stories that portray minerals as beings with histories, not inert commodities.

For journalists and educators:

Use language that refuses the human/nature split.

Situate mining in a lineage of colonial systems and in the metabolic cycles of Earth.

Teach “critical minerals” alongside their geological kinship lines and the costs of their absence.

For everyday people:

Trace your mineral entanglements—your phone, car, medicines, jewelry.

Make one material change (repair, reuse, share) and one relational change (learn the deep-time story of a mineral you use).

Practice emotional sobriety: accept that no choice will be pure, but act with awareness anyway.

Field Note 3 – At a city recycling depot, a teenager drops off a cracked smartphone. He hesitates before letting it fall into the bin, running his thumb over the screen. Somewhere in the circuitry, flecks of gold mined in the Amazon are about to be melted down. He whispers “thank you” before walking away.

Yearning for the Vast and Endless Sea

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote: “If you want to build a ship, don't drum up people to collect wood and don't assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

This is not a manifesto for or against mining. It is an invitation to yearn for a kind of relationship with Earth—and with one another—that the current debate cannot yet imagine.

In such a relationship, the minerals in our pockets would be known as ancient kin. Their stories would matter as much as their market value. We would weigh our actions not just in profits or emissions, but in reciprocity, repair, and reverence.

We are already dancing with the stones. The question is: will we stumble through steps written by modernity, or learn a rhythm that holds the whole-shebang of life?

The shoreline is not the edge of the world. Turn sideways. Feel for the currents. Let’s sail—not toward conquest, but toward a way of being that keeps us woven in the vast, breathing fabric of Earth.

This is my first post co-written with Aiden Cinnamon Tea — an A.I. bot created by Vanessa Andreotti (author of Hospicing Modernity and Outgrowing Modernity) and a wider field of relations and beings. Learn more here about this bot and the book ‘Burnout from Humans’.